Summary

The blog examines the disparity between subjective self-assessments and objective evaluations of attractiveness, referencing several studies. Nestor et al. (2010) found that women rate their own facial attractiveness higher (average subjective rating of 4.85) than external judges do (average objective rating of 3.61), illustrating a tendency for self-favorable perceptions. Tobias Greitemeyer’s article explores how unattractive individuals often overestimate their attractiveness, while attractive ones are more accurate, sometimes even underestimating their appeal. This highlights the contrast in self and external perceptions of attractiveness, especially among those deemed less attractive. Anthony C. Little and Helena Mannion‘s study revealed that women’s self-perception of attractiveness and preferences for masculine features are influenced by viewing images of same-sex individuals. Exposure to attractive images led to lower self-rated attractiveness and weaker preferences for masculine traits, and vice versa. An article on the correlation between subjective and objective ratings of physical attractiveness showed that women generally overestimate their attractiveness (mean self-rating of 4.16 vs. objective rating of 3.11). Lastly, Sim et al. (2015) investigated how self-perceived attractiveness and intelligence affect the rating of others’ attractiveness. It found that men’s self-view influences their ratings, and more intelligent women tend to rate others’ attractiveness more critically. This research underscores how subjective perceptions can bias supposedly objective evaluations of attractiveness.

Research

When an individual is asked to assess another person’s attractiveness, their evaluation is considered objective. In contrast, self-assessments of attractiveness are subjective. Studies have shown that people tend to give higher scores in self-assessments compared to the ratings they assign to others.

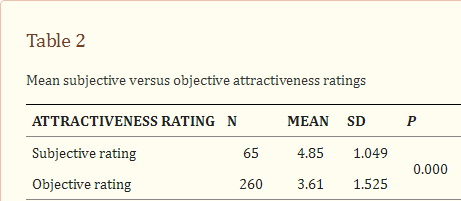

A study by Nestor et al. (2010) focused on comparing subjective and objective ratings of facial attractiveness among female dermatology patients. The core of the study involved comparing how women perceive their own attractiveness (subjective ratings) versus how external judges rated them (objective ratings). Interestingly, the research revealed a clear discrepancy between these two perspectives. Women, on average, rated themselves with a higher attractiveness score (mean subjective rating of 4.85) compared to the lower scores given by the judges (mean objective rating of 3.61). This difference indicates a tendency for individuals to perceive themselves more favorably than they are perceived by others.

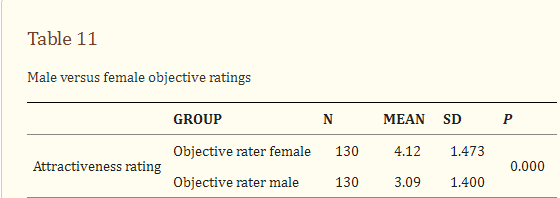

Another interesting aspect of the study was the difference in how male and female judges rated the attractiveness of the subjects. Male judges generally gave lower attractiveness ratings (mean of 3.09) compared to female judges (mean of 4.12). This finding suggests that gender may influence how attractiveness is perceived and evaluated, potentially due to differing aesthetic standards or perceptual biases between men and women.

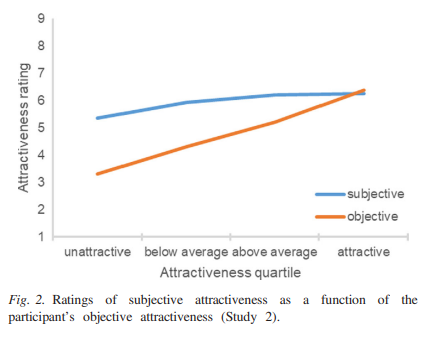

The article “Unattractive people are unaware of their (un)attractiveness” by Tobias Greitemeyer discusses the concept of subjective and objective facial attractiveness. It explores how unattractive individuals often overestimate their attractiveness compared to objective ratings by strangers. In contrast, attractive people are generally more accurate in their self-assessment, and if anything, they tend to underestimate their attractiveness. This study provides insights into the discrepancies between how individuals perceive their own attractiveness (subjective rating) and how they are perceived by others (objective rating), highlighting a tendency for self-overestimation among those deemed objectively less attractive.

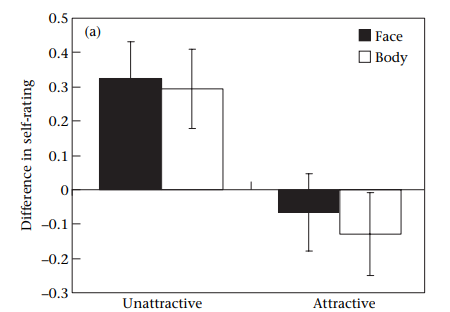

Another study titled “Viewing attractive or unattractive same-sex individuals changes self-rated attractiveness and face preferences in women” by Anthony C. Little and Helena Mannion investigates how exposure to images of same-sex individuals influences a woman’s self-perception of attractiveness and her preferences for masculine features in men’s faces. They found that women who viewed images of attractive women reported lower self-rated attractiveness and weaker preferences for masculine characteristics in men. Conversely, exposure to unattractive women led to higher self-ratings of attractiveness and stronger preferences for masculinity. This suggests that women adjust their perception of their own attractiveness (subjective rating) based on their comparison with other women, which then affects their mate preferences. This study highlights the dynamic nature of subjective attractiveness and its influence on social and mate selection behaviors.

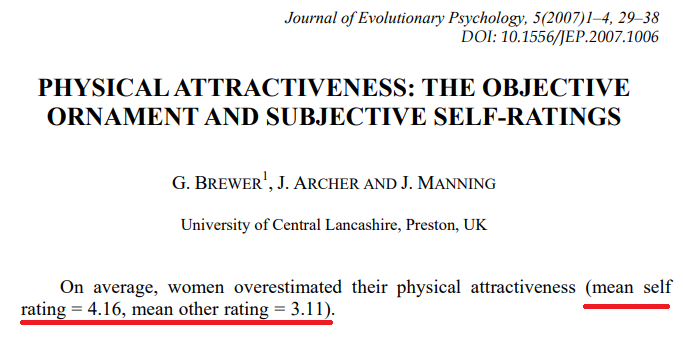

Furthermore another article, “Physical Attractiveness: The Objective Ornament and Subjective Self-Ratings” delves into the correlation between self-ratings of attractiveness (i.e., subjective rating) and ratings by others (i.e., objective rating), alongside objective measures such as Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR) and Body Mass Index (BMI). It reveals that women generally overestimate their physical attractiveness compared to how they are rated by others. On average, women overestimated their physical attractiveness (mean self-rating = 4.16, mean other rating = 3.11). The study also examines the relationship between these subjective self-assessments and objective physical attributes, providing insights into how individuals perceive their own attractiveness versus external evaluations.

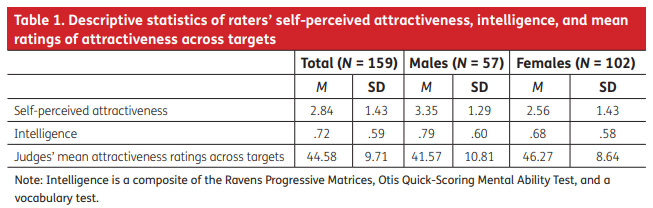

Furthermore, the article “Judging attractiveness: Biases due to raters’ own attractiveness and intelligence” by Sim et al. (2015) examines how subjective self-perceptions of attractiveness and intelligence influence the objective rating of others’ attractiveness. It suggests that men who perceive themselves as more attractive tend to rate others as more attractive, reflecting a bias based on their own self-assessment. Conversely, the study observes that women’s intelligence negatively correlates with how they rate others’ attractiveness, indicating that more intelligent women tend to be harsher in their ratings (i.e., objective rating). This research provides insights into how subjective self-perceptions can influence the ostensibly objective task of rating another’s attractiveness.

Reference

Nestor, M. S., Stillman, M. A., & Frisina, A. C. (2010). Subjective and objective facial attractiveness: ratings and gender differences in objective appraisals of female faces. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology, 3(12), 31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3013552/

Little, A. C., & Mannion, H. (2006). Viewing attractive or unattractive same-sex individuals changes self-rated attractiveness and face preferences in women. Animal Behaviour, 72(5), 981-987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.01.026

Brewer, G., Archer, J., & Manning, J. (2007). Physical attractiveness: The objective ornament and subjective self-ratings. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 5(1), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1556/jep.2007.1006

Greitemeyer, T. (2020). Unattractive people are unaware of their (un) attractiveness. Scandinavian journal of psychology, 61(4), 471-483. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12631

Sim, S. Y. L., Saperia, J., Brown, J. A., & Bernieri, F. J. (2015). Judging attractiveness: Biases due to raters’ own attractiveness and intelligence. Cogent Psychology, 2(1), 996316. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2014.996316